Reading time: 15 min

There was once a young fellow who enlisted as a soldier, conducted himself bravely, and was always the foremost when it rained bullets. So long as the war lasted, all went well, but when peace was made, he received his dismissal, and the captain said he might go where he liked. His parents were dead, and he had no longer a home, so he went to his brothers and begged them to take him in, and keep him until war broke out again. The brothers, however, were hard-hearted and said, „What can we do with thee? thou art of no use to us; go and make a living for thyself.“ The soldier had nothing left but his gun. He took that on his shoulder, and went forth into the world. He came to a wide heath, on which nothing was to be seen but a circle of trees; under these he sat sorrowfully down, and began to think over his fate. „I have no money,“ thought he, „I have learnt no trade but that of fighting, and now that they have made peace they don’t want me any longer. So I see beforehand that I shall have to starve.“ All at once he heard a rustling, and when he looked round, a strange man stood before him, who wore a green coat and looked right stately, but had a hideous cloven foot. „I know already what thou art in need of,“ said the man; „gold and possessions shall thou have, as much as thou canst make away with do what thou wilt, but first I must know if thou art fearless, that I may not bestow my money in vain.“ – „A soldier and fear – how can those two things go together?“ he answered; „thou canst put me to the proof.“ – „Very well, then,“ answered the man, „look behind thee.“ The soldier turned round, and saw a large bear, which came growling towards him. „Oho!“ cried the soldier, „I will tickle thy nose for thee, so that thou shalt soon lose thy fancy for growling,“ and he aimed at the bear and shot it through the muzzle. It fell down and never stirred again. „I see quite well,“ said the stranger, „that thou art not wanting in courage, but there is still another condition which thou wilt have to fulfil.“ – „If it does not endanger my salvation,“ replied the soldier, who knew very well who was standing by him. „If it does, I’ll have nothing to do with it.“ – „Thou wilt look to that for thyself,“ answered Greencoat; „thou shalt for the next seven years neither wash thyself, nor comb thy beard, nor thy hair, nor cut thy nails, nor say one paternoster. I will give thee a coat and a cloak, which during this time thou must wear. If thou diest during these seven years, thou art mine. If thou remainest alive, thou art free, and rich to boot, for all the rest of thy life.“ The soldier thought of the great extremity in which he now found himself, and as he so often had gone to meet death, he resolved to risk it now also, and agreed to the terms. The Devil took off his green coat, gave it to the soldier, and said, „If thou hast this coat on thy back and puttest thy hand into the pocket, thou wilt always find it full of money.“ Then he pulled the skin off the bear and said, „This shall be thy cloak, and thy bed also, for thereon shalt thou sleep, and in no other bed shalt thou lie, and because of this apparel shalt thou be called Bearskin.“ After this the Devil vanished.

The soldier put the coat on, felt at once in the pocket, and found that the thing was really true. Then he put on the bearskin and went forth into the world, and enjoyed himself, refraining from nothing that did him good and his money harm. During the first year his appearance was passable, but during the second he began to look like a monster. His hair covered nearly the whole of his face, his beard was like a piece of coarse felt, his fingers had claws, and his face was so covered with dirt that if cress had been sown on it, it would have come up. Whosoever saw him, ran away, but as he everywhere gave the poor money to pray that he might not die during the seven years, and as he paid well for everything he still always found shelter. In the fourth year, he entered an inn where the landlord would not receive him, and would not even let him have a place in the stable, because he was afraid the horses would be scared. But as Bearskin thrust his hand into his pocket and pulled out a handful of ducats, the host let himself be persuaded and gave him a room in an outhouse. Bearskin was, however, obliged to promise not to let himself be seen, lest the inn should get a bad name.

As Bearskin was sitting alone in the evening, and wishing from the bottom of his heart that the seven years were over, he heard a loud lamenting in a neighboring room. He had a compassionate heart, so he opened the door, and saw an old man weeping bitterly, and wringing his hands. Bearskin went nearer, but the man sprang to his feet and tried to escape from him. At last when the man perceived that Bearskin’s voice was human he let himself be prevailed on, and by kind words bearskin succeeded so far that the old man revealed the cause of his grief. His property had dwindled away by degrees, he and his daughters would have to starve, and he was so poor that he could not pay the innkeeper, and was to be put in prison. „If that is your only trouble,“ said Bearskin, „I have plenty of money.“ He caused the innkeeper to be brought thither, paid him and put a purse full of gold into the poor old man’s pocket besides.

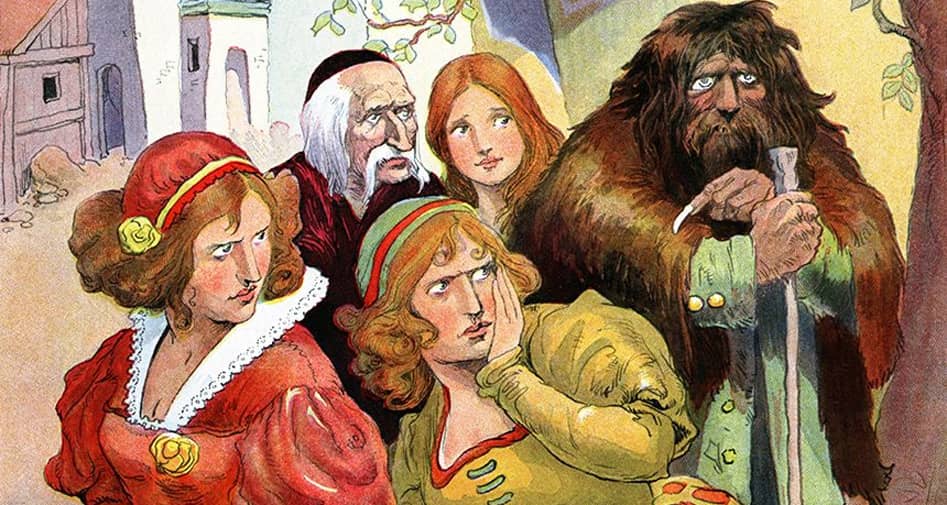

When the old man saw himself set free from all his troubles he did not know how to be grateful enough. „Come with me,“ said he to Bearskin; „my daughters are all miracles of beauty, choose one of them for thyself as a wife. When she hears what thou hast done for me, she will not refuse thee. Thou dost in truth look a little strange, but she will soon put thee to rights again.“ This pleased Bearskin well, and he went. When the eldest saw him she was so terribly alarmed at his face that she screamed and ran away. The second stood still and looked at him from head to foot, but then she said, „How can I accept a husband who no longer has a human form? The shaven bear that once was here and passed itself off for a man pleased me far better, for at any rate it wore a hussar’s dress and white gloves. If it were nothing but ugliness, I might get used to that.“ The youngest, however, said, „Dear father, that must be a good man to have helped you out of your trouble, so if you have promised him a bride for doing it, your promise must be kept.“ It was a pity that Bearskin’s face was covered with dirt and with hair, for if not they might have seen how delighted he was when he heard these words. He took a ring from his finger, broke it in two, and gave her one half, the other he kept for himself. He wrote his name, however, on her half, and hers on his, and begged her to keep her piece carefully, and then he took his leave and said, „I must still wander about for three years, and if I do not return then, thou art free, for I shall be dead. But pray to God to preserve my life.“

The poor betrothed bride dressed herself entirely in black, and when she thought of her future bridegroom, tears came into her eyes. Nothing but contempt and mockery fell to her lot from her sisters. „Take care,“ said the eldest, „if thou givest him thy hand, he will strike his claws into it.“ – „Beware!“ said the second. „Bears like sweet things, and if he takes a fancy to thee, he will eat thee up.“ – „Thou must always do as he likes,“ began the elder again, „or else he will growl.“ And the second continued, „But the wedding will be a merry one, for bears dance well.“ The bride was silent, and did not let them vex her. Bearskin, however, travelled about the world from one place to another, did good where he was able, and gave generously to the poor that they might pray for him.

At length, as the last day of the seven years dawned, he went once more out on to the heath, and seated himself beneath the circle of trees. It was not long before the wind whistled, and the Devil stood before him and looked angrily at him. Then he threw Bearskin his old coat, and asked for his own green one back. „We have not got so far as that yet,“ answered Bearskin, „thou must first make me clean.“ Whether the Devil liked it or not, he was forced to fetch water, and wash Bearskin, comb his hair, and cut his nails. After this, he looked like a brave soldier, and was much handsomer than he had ever been before.

When the Devil had gone away, Bearskin was quite lighthearted. He went into the town, put on a magnificent velvet coat, seated himself in a carriage drawn by four white horses, and drove to his bride’s house. No one recognized him, the father took him for a distinguished general, and led him into the room where his daughters were sitting. He was forced to place himself between the two eldest, they helped him to wine, gave him the best pieces of meat, and thought that in all the world they had never seen a handsomer man. The bride, however, sat opposite to him in her black dress, and never raised her eyes, nor spoke a word. When at length he asked the father if he would give him one of his daughters to wife, the two eldest jumped up, ran into their bedrooms to put on splendid dresses, for each of them fancied she was the chosen one. The stranger, as soon as he was alone with his bride, brought out his half of the ring, and threw it in a glass of wine which he reached across the table to her. She took the wine, but when she had drunk it, and found the half ring lying at the bottom, her heart began to beat. She got the other half, which she wore on a ribbon round her neck, joined them, and saw that the two pieces fitted exactly together. Then said he, „I am thy betrothed bridegroom, whom thou sawest as Bearskin, but through God’s grace I have again received my human form, and have once more become clean.“ He went up to her, embraced her, and gave her a kiss. In the meantime the two sisters came back in full dress, and when they saw that the handsome man had fallen to the share of the youngest, and heard that he was Bearskin, they ran out full of anger and rage. One of them drowned herself in the well, the other hanged herself on a tree. In the evening, some one knocked at the door, and when the bridegroom opened it, it was the Devil in his green coat, who said, „Seest thou, I have now got two souls in the place of thy one!“

Learn languages. Double-tap on a word.Learn languages in context with Childstories.org and Deepl.com.

Learn languages. Double-tap on a word.Learn languages in context with Childstories.org and Deepl.com.Backgrounds

Interpretations

Adaptions

Summary

Linguistics

„Bearskin“ is a German fairy tale collected by the Brothers Grimm, Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm, who were linguists, cultural researchers, and authors. The tale is also known as „Der Bärenhäuter“ in German, which translates to „The Bear-Skinner“ or „The Man in the Bear’s Skin.“ The Brothers Grimm included the story in their collection „Kinder- und Hausmärchen“ (Children’s and Household Tales), first published in 1812.

The Brothers Grimm were prominent figures during the German Romantic movement in the early 19th century. They aimed to preserve German folklore, which they believed represented the cultural heritage and identity of the German people. Their collection of fairy tales was gathered through oral and written sources, including stories told by peasants, friends, and family members.

„Bearskin“ is one of more than 200 stories in the Grimm brothers‘ collection, which also includes famous tales like „Cinderella,“ „Snow White,“ „Hansel and Gretel,“ and „Rapunzel.“ Over time, the collection has been revised and expanded, with the final edition published in 1857 containing 210 stories.

The Grimm brothers‘ fairy tales have had a significant impact on the literary world and have been translated into more than 100 languages. Their work has inspired countless adaptations, including stage plays, films, and television shows. The stories continue to be popular today, resonating with readers and audiences for their timeless themes, moral lessons, and fantastical elements.

„Bearskin“ can be interpreted in various ways, touching on themes such as inner beauty, redemption, sacrifice, and the battle between good and evil.

Inner Beauty: The tale emphasizes the importance of looking beyond external appearances to recognize a person’s true character. The youngest daughter, unlike her superficial sisters, agrees to marry Bearskin because of his kindness and good deeds, despite his monstrous appearance. This highlights the moral that inner beauty and virtue are more important than outward appearances.

Redemption: Bearskin’s story is one of redemption, as he is ultimately transformed from a desperate soldier to a wealthy, noble man. His willingness to endure suffering and maintain his goodness, even while under the Devil’s influence, demonstrates the power of resilience and the possibility of redemption.

Sacrifice: Bearskin agrees to the Devil’s terms to escape poverty, putting his soul and future at risk. Throughout the seven years, he endures isolation, humiliation, and the constant threat of death. His sacrifice highlights the importance of taking risks and making difficult choices for a better future.

Good vs. Evil: The story illustrates the struggle between good and evil, with Bearskin representing the forces of good and the Devil representing evil. Despite the Devil’s efforts to claim Bearskin’s soul, Bearskin’s kindness, generosity, and determination ultimately prevail. This theme underscores the notion that good can triumph over evil, even when faced with seemingly insurmountable challenges.

The Power of Love: The love between Bearskin and his bride serves as a powerful force for good. Her willingness to marry him despite his appearance and the strength of their bond ultimately help him survive the seven years and defeat the Devil. This theme highlights the transformative and redemptive power of love.

Overall, „Bearskin“ is a complex tale that offers multiple layers of interpretation, exploring themes that are still relevant today. The story encourages readers to look beyond appearances, embrace sacrifice, and believe in the power of love and goodness to overcome adversity.

The fairy tale „Bearskin“ by the Brothers Grimm has been adapted and reimagined in various forms of media. Here are some examples.

Film adaptations: The story has been adapted into several films, including the 1983 German film „Bärskin,“ the 2010 British film „Heartless,“ and the 2017 short film „Bearskin“ directed by Daniel Stankler.

Literature adaptations: The tale has been retold and adapted in various books, including „Barefoot: A Story of Surrendering to God“ by Sharon Garlough Brown and „The Soldier and the Bear“ by Helen Ward.

Musical adaptations: The story has also been adapted into a musical. „Bearskin: A New Musical“ premiered at the London Theater Workshop in 2015 and was later staged at the Hope Theater in London.

Television adaptations: The story has been adapted into television shows, such as „Faerie Tale Theater“ in 1984, where it was retold as „The Soldier and Death,“ and „Grimm“ in 2012, where it was adapted into an episode titled „Bearskin.“

Art adaptations: The tale has also been adapted into art forms, such as paintings and illustrations. For example, the French artist Gustave Doré illustrated the tale in the 19th century, and German artist Carl Offterdinger painted a series of scenes from the story.

Overall, the enduring popularity of „Bearskin“ has inspired many creative adaptations that have allowed new generations to enjoy and interpret the timeless tale in their own ways.

„Bearskin“ is a fairy tale by the Brothers Grimm about a young soldier who, after being dismissed from service when peace is declared, finds himself without a home or means of support. He encounters the Devil, who offers him wealth in exchange for wearing a bearskin and not grooming himself for seven years, during which time he must not pray. If he dies during this period, his soul belongs to the Devil, but if he survives, he will be free and wealthy.

Despite his monstrous appearance, the soldier, now known as Bearskin, uses his newfound wealth to help others, including an impoverished old man who offers him one of his beautiful daughters as a wife. The youngest daughter agrees to marry Bearskin, despite his appearance, and they exchange halves of a broken ring as a token of their betrothal. Bearskin then continues his journey, helping the poor and hoping to survive the seven years.

On the last day of the seven years, the Devil reluctantly cleans Bearskin, restoring him to his former handsome appearance. Bearskin returns to his bride, now a wealthy and distinguished-looking man, and reveals his true identity to her by reuniting the halves of the ring. The couple rejoices, while the bride’s envious sisters, who had ridiculed her for agreeing to marry Bearskin, end up taking their own lives out of despair.

In the end, the Devil ironically knocks on their door, informing Bearskin that he has gained two souls – those of the sisters – in place of the one he lost. Bearskin and his bride ultimately triumph over the Devil, and their love and devotion to one another are rewarded.

The fairy tale „Bearskin“ by the Brothers Grimm presents a rich opportunity for linguistic analysis, exploring its language use, narrative structure, and thematic elements.

Here’s an in-depth analysis:

Language and Style:

Archaic Language: The story employs an archaic style, characteristic of 19th-century German tales. Phrases like „thou art“ and „shalt“ reflect the formal and biblical tone often found in folk tales of this era.

Symbolic Language: The use of symbols is prominent, such as the green coat and bearskin, representing wealth and a cursed state, respectively. The cloven foot of the strange man indicates his demonic nature, a common symbol in folklore.

Descriptive Imagery: Visual descriptions, such as the soldier’s transformation into a hairy, monstrous figure, are vivid and emphasize his physical and moral degradation.

Narrative Structure:

Classic Folklore Structure: The tale follows a typical folklore structure with an introduction, conflict, climax, and resolution. The soldier’s initial plight sets the stage, the bargain introduces the conflict, and his eventual redemption offers resolution.

Moral Undertones: The narrative is didactic, warning against greed and emphasizing redemption through good deeds. The protagonist’s journey reflects a moral ascent, despite his initial fall.

Character Archetypes: The tale features common archetypes, including the „devil/stranger“ as the tempter, the „soldier“ as the brave, yet flawed hero, and the „bride“ as the virtuous maiden.

Thematic Elements:

Redemption and Transformation: Central to the tale is the theme of transformation. The soldier’s physical uncleanliness symbolizes his moral state, and his eventual cleansing marks his redemption.

Good vs. Evil: The interaction between the soldier and the devil highlights the struggle between good and evil, with the soldier’s soul at stake.

Fear and Courage: The soldier’s fearlessness contrasts with his brothers‘ cowardice and the societal fear of his monstrous appearance. His courage ultimately leads to his salvation.

Social Commentary: The tale offers commentary on societal values, reflecting the harsh realities faced by soldiers post-war and critiquing superficial judgments based on appearances.

Cultural and Historical Context:

Role of Soldiers: The story reflects the historical context of soldiers being dismissed after wars, a reality for many in the post-Napoleonic era when this tale was recorded.

Religious Influences: The invocation of prayers and the presence of demonic figures underscore the religious influences prevalent in Grimm’s tales, reflecting a world where moral and spiritual battles are paramount.

Dialogue and Interaction:

Direct Speech: Dialogue in the story enhances character development. The soldier’s bravado („A soldier and fear – how can those two things go together?“) defines his fearless nature.

Transactional Exchanges: The interactions, particularly between Bearskin and other characters, are often transactional. The offer of money in exchange for prayers or the bride reflects societal and moral exchanges.

Overall, „Bearskin“ is a complex tale interwoven with themes of redemption, courage, and social critique, framed within the linguistic and narrative style characteristic of the Brothers Grimm. Through its symbolic language and archetypal characters, it delivers moral lessons while capturing the socio-cultural essence of its time.

Information for scientific analysis

Fairy tale statistics | Value |

|---|---|

| Number | KHM 101 |

| Aarne-Thompson-Uther-Index | ATU Typ 361 |

| Translations | DE, EN, DA, ES, FR, PT, IT, JA, NL, PL, RU, TR, VI, ZH |

| Readability Index by Björnsson | 34 |

| Flesch-Reading-Ease Index | 79 |

| Flesch–Kincaid Grade-Level | 7.8 |

| Gunning Fog Index | 10.5 |

| Coleman–Liau Index | 7.7 |

| SMOG Index | 8.6 |

| Automated Readability Index | 8.5 |

| Character Count | 10.300 |

| Letter Count | 7.914 |

| Sentence Count | 89 |

| Word Count | 1.982 |

| Average Words per Sentence | 22,27 |

| Words with more than 6 letters | 232 |

| Percentage of long words | 11.7% |

| Number of Syllables | 2.465 |

| Average Syllables per Word | 1,24 |

| Words with three Syllables | 78 |

| Percentage Words with three Syllables | 3.9% |

Facebook

Facebook  Whatsapp

Whatsapp  Messenger

Messenger  Telegram

Telegram Reddit

Reddit