Reading time: 10 min

Once upon a time lived a peasant and his wife, and the parson of the village had a fancy for the wife, and had wished for a long while to spend a whole day happily with her. The peasant woman, too, was quite willing. One day, therefore, he said to the woman, „Listen, my dear friend, I have now thought of a way by which we can for once spend a whole day happily together. I’ll tell you what. On Wednesday, you must take to your bed, and tell your husband you are ill, and if you only complain and act being ill properly, and go on doing so until Sunday when I have to preach, I will then say in my sermon that whosoever has at home a sick child, a sick husband, a sick wife, a sick father, a sick mother, a sick brother or whosoever else it may be, and makes a pilgrimage to the Göckerli hill in Italy, where you can get a peck of laurel-leaves for a kreuzer, the sick child, the sick husband, the sick wife, the sick father, or sick mother, the sick sister, or whosoever else it may be, will be restored to health immediately.“

„I will manage it,“ said the woman promptly. Now therefore on the Wednesday, the peasant woman took to her bed, and complained and lamented as agreed on, and her husband did everything for her that he could think of, but nothing did her any good, and when Sunday came the woman said, „I feel as ill as if I were going to die at once, but there is one thing I should like to do before my end I should like to hear the parson’s sermon that he is going to preach today.“ On that the peasant said, „Ah, my child, do not do it — thou mightest make thyself worse if thou wert to get up. Look, I will go to the sermon, and will attend to it very carefully, and will tell thee everything the parson says.“

„Well,“ said the woman, „go, then, and pay great attention, and repeat to me all that thou hearest.“ So the peasant went to the sermon, and the parson began to preach and said, if any one had at home a sick child, a sick husband, a sick wife, a sick father a sick mother, a sick sister, brother or any one else, and would make a pilgimage to the Göckerli hill in Italy, where a peck of laurel-leaves costs a kreuzer, the sick child, sick husband, sick wife, sick father, sick mother, sick sister, brother, or whosoever else it might be, would be restored to health instantly, and whosoever wished to undertake the journey was to go to him after the service was over, and he would give him the sack for the laurel-leaves and the kreuzer.

Then no one was more rejoiced than the peasant, and after the service was over, he went at once to the parson, who gave him the bag for the laurel-leaves and the kreuzer. After that he went home, and even at the house door he cried, „Hurrah! dear wife, it is now almost the same thing as if thou wert well! The parson has preached today that whosoever had at home a sick child, a sick husband, a sick wife, a sick father, a sick mother, a sick sister, brother or whoever it might be, and would make a pilgrimage to the Göckerli hill in Italy, where a peck of laurel-leaves costs a kreuzer, the sick child, sick husband, sick wife, sick father, sick mother, sick sister, brother, or whosoever else it was, would be cured immediately, and now I have already got the bag and the kreuzer from the parson, and will at once begin my journey so that thou mayst get well the faster,“ and thereupon he went away. He was, however, hardly gone before the woman got up, and the parson was there directly.

But now we will leave these two for a while, and follow the peasant, who walked on quickly without stopping, in order to get the sooner to the Göckerli hill, and on his way he met his gossip. His gossip was an egg-merchant, and was just coming from the market, where he had sold his eggs. „May you be blessed,“ said the gossip, „where are you off to so fast?“

„To all eternity, my friend,“ said the peasant, „my wife is ill, and I have been today to hear the parson’s sermon, and he preached that if any one had in his house a sick child, a sick husband, a sick wife, a sick father, a sick mother, a sick sister, brother or any one else, and made a pilgrimage to the Göckerli hill in Italy, where a peck of laurel-leaves costs a kreuzer, the sick child, the sick husband, the sick wife, the sick father, the sick mother, the sick sister, brother or whosoever else it was, would be cured immediately, and so I have got the bag for the laurel-leaves and the kreuzer from the parson, and now I am beginning my pilgrimage.“ – „But listen, gossip,“ said the egg-merchant to the peasant, „are you, then, stupid enough to believe such a thing as that? Don’t you know what it means? The parson wants to spend a whole day alone with your wife in peace, so he has given you this job to do to get you out of the way.“

„My word!“ said the peasant. „How I’d like to know if that’s true!“

„Come, then,“ said the gossip, „I’ll tell you what to do. Get into my egg-basket and I will carry you home, and then you will see for yourself.“ So that was settled, and the gossip put the peasant into his egg-basket and carried him home.

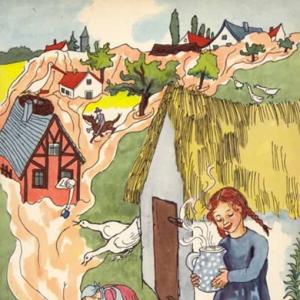

When they got to the house, hurrah! but all was going merry there! The woman had already had nearly everything killed that was in the farmyard, and had made pancakes, and the parson was there, and had brought his fiddle with him. The gossip knocked at the door, and woman asked who was there. „It is I, gossip,“ said the egg-merchant, „give me shelter this night. I have not sold my eggs at the market, so now I have to carry them home again, and they are so heavy that I shall never be able to do it, for it is dark already.“

„Indeed, my friend,“ said the woman, „thou comest at a very inconvenient time for me, but as thou art here it can’t be helped, come in, and take a seat there on the bench by the stove.“ Then she placed the gossip and the basket which he carried on his back on the bench by the stove. The parso, however, and the woman, were as merry as possible. At length the parson said, „Listen, my dear friend, thou canst sing beautifully; sing something to me.“ – „Oh,“ said the woman, „I cannot sing now, in my young days indeed I could sing well enough, but that’s all over now.“

„Come,“ said the parson once more, „do sing some little song.“

On that the woman began and sang,

„I’ve sent my husband away from me

To the Göckerli hill in Italy.“

Thereupon the parson sang:

„I wish ‚twas a year before he came back,

I’d never ask him for the laurel-leaf sack.“

Hallelujah. Then the gossip who was in the background began to sing (but I ought to tell you the peasant was called Hildebrand), so the gossip sang,

„What art thou doing, my Hildebrand dear,

There on the bench by the stove so near?“

Hallelujah. And then the peasant sang from his basket, „All singing I ever shall hate from this day, And here in this basket no longer I’ll stay.“

Hallelujah. And he got out of the basket, and cudgelled the parson out of the house.

Learn languages. Double-tap on a word.Learn languages in context with Childstories.org and Deepl.com.

Learn languages. Double-tap on a word.Learn languages in context with Childstories.org and Deepl.com.Backgrounds

Interpretations

Adaptions

Summary

Linguistics

„Old Hildebrand“ is a lesser-known fairy tale by the Brothers Grimm, also known as Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm. The Brothers Grimm were German linguists, cultural researchers, and authors who lived in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. They are best known for their collection of folk tales and fairy tales, which were published under the title „Kinder- und Hausmärchen“ or „Children’s and Household Tales“ in 1812. The collection has gone through numerous editions and contains some of the most famous fairy tales, such as „Cinderella,“ „Snow White,“ „Rapunzel,“ and „Hansel and Gretel.“

„Old Hildebrand“ features a tale of deceit, betrayal, and the ultimate exposure of a dishonest plan. The story serves as a cautionary tale, using humor and satire to explore human relationships and the consequences of dishonest behavior.

The Brothers Grimm collected their stories from various sources, often based on traditional oral folk tales that had been passed down through generations. Their work aimed to preserve the cultural heritage of Germany and offer moral lessons and entertainment to readers. The tales have since been translated into numerous languages, adapted into various forms of media, and have become an integral part of Western storytelling tradition.

„Old Hildebrand“ can be interpreted in various ways, highlighting different aspects of human behavior, relationships, and the consequences of deceit:

Deceit and betrayal: The story serves as a cautionary tale about the consequences of deceit and betrayal. The parson and the wife’s plan to deceive the husband is eventually exposed, resulting in embarrassment and punishment for the parson. The story suggests that dishonesty will eventually be revealed, and those who deceive others will face the consequences of their actions.

Trust in relationships: The peasant’s trust in his wife and the parson is exploited for their selfish desires. The story highlights the importance of trust in relationships, both romantic and otherwise, and the damage that can be done when that trust is broken.

The importance of vigilance: The peasant’s gossip, an unlikely ally, serves as a reminder to remain vigilant and be aware of the intentions of those around us. The gossip’s keen perception of the parson’s intentions ultimately saves the peasant from being duped.

The role of humor and satire: The story uses humor and satire to address serious themes. The characters‘ songs, especially the ones mocking the peasant’s absence, provide comic relief while also driving the story towards its conclusion. The use of humor and satire makes the story entertaining while still conveying important messages about trust, betrayal, and the consequences of dishonesty.

The consequences of selfish desires: Both the parson and the wife display selfishness by prioritizing their desires over the well-being of the husband. The story shows that acting on selfish desires can lead to negative consequences not only for the individuals involved but also for the relationships they share with others.

„Old Hildebrand“ has inspired several adaptations in various forms of media over the years. Here are some notable adaptations:

„The Dragon Slayer“ by Martyn Ford: This children’s book adaptation of „Old Hildebrand“ tells the story of a young boy named Ralph who sets out to slay a dragon with the help of an old knight named Hildebrand. The book is illustrated by Michael Foreman and offers a modern retelling of the classic fairy tale.

„Dragon Slayer“ (1981): This British fantasy film, directed by Matthew Robbins, is loosely based on the tale of „Old Hildebrand“. The film tells the story of a young prince named Galen who sets out to kill a dragon that is terrorizing his kingdom. He is aided by an old knight named Ulrich and a young woman named Valerian. The film was a box office success and won the Academy Award for Best Visual Effects.

„Dragon Slayer: The Legend of Heroes“ (1990): This Japanese role-playing video game was released for the Super Nintendo Entertainment System and is loosely based on the tale of „Old Hildebrand“. The game follows a young hero named Ryu who sets out to slay a dragon with the help of an old warrior named Bo. The game was well-received and is considered a classic of the RPG genre.

„Old Hildebrand“ (2018): This short film adaptation of the fairy tale was directed by Kaleb Lechowski and produced by the Blender Foundation. The film is an animated retelling of the classic tale that updates the story with modern graphics and animation techniques.

These adaptations demonstrate the enduring appeal of the classic fairy tale of „Old Hildebrand“ and its ability to inspire new and creative interpretations across different media platforms.

In „Old Hildebrand“ by Brothers Grimm, a peasant lives with his wife who has caught the attention of the village parson. The parson and the woman wish to spend a day together, so they devise a plan to fake the woman’s illness. The parson promises to announce in his sermon that whoever has a sick relative can cure them by fetching laurel-leaves from the Göckerli hill in Italy. As expected, the woman pretends to be sick, and the peasant, desperate to cure her, attends the sermon and sets off on the journey.

However, the peasant soon meets his gossip, an egg-merchant, who explains that the parson’s plan is a ruse to spend time with the peasant’s wife. The gossip convinces the peasant to hide in his egg-basket and carries him home, where they find the parson and the wife enjoying themselves, feasting and playing music.

When the parson and the woman sing songs mocking the peasant’s absence, the gossip and the peasant join in, revealing the husband’s presence. Upon realizing the deceit, the peasant emerges from the basket and chases the parson out of his house.

The fairy tale „Old Hildebrand“ from the Brothers Grimm presents a rich field for linguistic analysis. This tale can be dissected from several linguistic perspectives:

Narrative Structure: The tale follows a traditional narrative structure with an introduction (setting up the characters and the parson’s plan), a complication (Hildebrand’s journey), a climax (the discovery of the ruse), and a resolution (Hildebrand’s return and the parson’s punishment). The structure uses repetition, a common technique in fairy tales, which enhances memorability and adds humor. The repeated mention of „a sick child, a sick husband, a sick wife,“ etc. , emphasizes the absurdity of the parson’s plan and the gullibility of the peasant.

Characterization through Dialogue: Characters are distinguished through their speech. The parson’s cunning is conveyed through his articulate and persuasive language, whereas the peasant’s straightforward and earnest speech reflects his simplicity and naivety. The dialogue aids in revealing motivations and societal roles, such as the parson assuming authority and the peasant as the obedient, unsuspecting husband.

Use of Irony and Humor: The tale uses dramatic irony; the audience is aware of the parson’s deceitful plan, while Hildebrand remains oblivious until his gossip enlightens him. Humor is derived from the situation’s absurdity, particularly the lengths to which the peasant goes based on the parson’s advice. The verbal humor in the songs further adds layers of amusement.

Symbolism and Themes: The pilgrimage to the Göckerli hill symbolizes both physical and metaphorical gullibility. It represents the journey of realization for Hildebrand. Themes of deception, fidelity, and social roles are evident. The tale critiques clerical authority and the vulnerability of simple folk to manipulation.

Syntax and Style: The story employs simple and repetitive syntax typical of oral storytelling. This choice facilitates easy understanding and memorization, important for a tale meant to be passed down orally. Descriptive language is minimized, with actions and dialogue driving the plot, a style that encourages listener engagement and imagination.

Cultural and Historical Context: The tale reflects cultural attitudes toward marriage, gender roles, and the clergy at the time it was written. The parson’s misuse of his position indicates a critical view of the church’s moral authority. The playful resolution, where the peasant gains the upper hand, serves as a moral lesson on the value of cleverness and awareness.

In summary, „Old Hildebrand“ employs linguistic elements that align with the oral traditions of fairy tales, characterized by repetition, simple structure, and moral undercurrents. The interplay of dialogue, symbolism, and narrative devices creates a humorous yet insightful commentary on human nature and social dynamics.

Information for scientific analysis

Fairy tale statistics | Value |

|---|---|

| Number | KHM 95 |

| Aarne-Thompson-Uther-Index | ATU Typ 1360C |

| Translations | DE, EN, DA, ES, PT, IT, JA, NL, PL, RU, TR, VI, ZH |

| Readability Index by Björnsson | 36.5 |

| Flesch-Reading-Ease Index | 71 |

| Flesch–Kincaid Grade-Level | 9.9 |

| Gunning Fog Index | 11.9 |

| Coleman–Liau Index | 7.4 |

| SMOG Index | 9.6 |

| Automated Readability Index | 10.2 |

| Character Count | 6.971 |

| Letter Count | 5.266 |

| Sentence Count | 51 |

| Word Count | 1.337 |

| Average Words per Sentence | 26,22 |

| Words with more than 6 letters | 138 |

| Percentage of long words | 10.3% |

| Number of Syllables | 1.726 |

| Average Syllables per Word | 1,29 |

| Words with three Syllables | 63 |

| Percentage Words with three Syllables | 4.7% |

Facebook

Facebook  Whatsapp

Whatsapp  Messenger

Messenger  Telegram

Telegram Reddit

Reddit